- What is the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)?

- How do I use multiple threads in Python?

- Understand the basics of computer architecture.

- Understand the GIL.

- Understand the difference between

threadsandprocessesin Python. Specifically how to manage these with theconcurrent.futureslibrary.

A bit of computer architecture

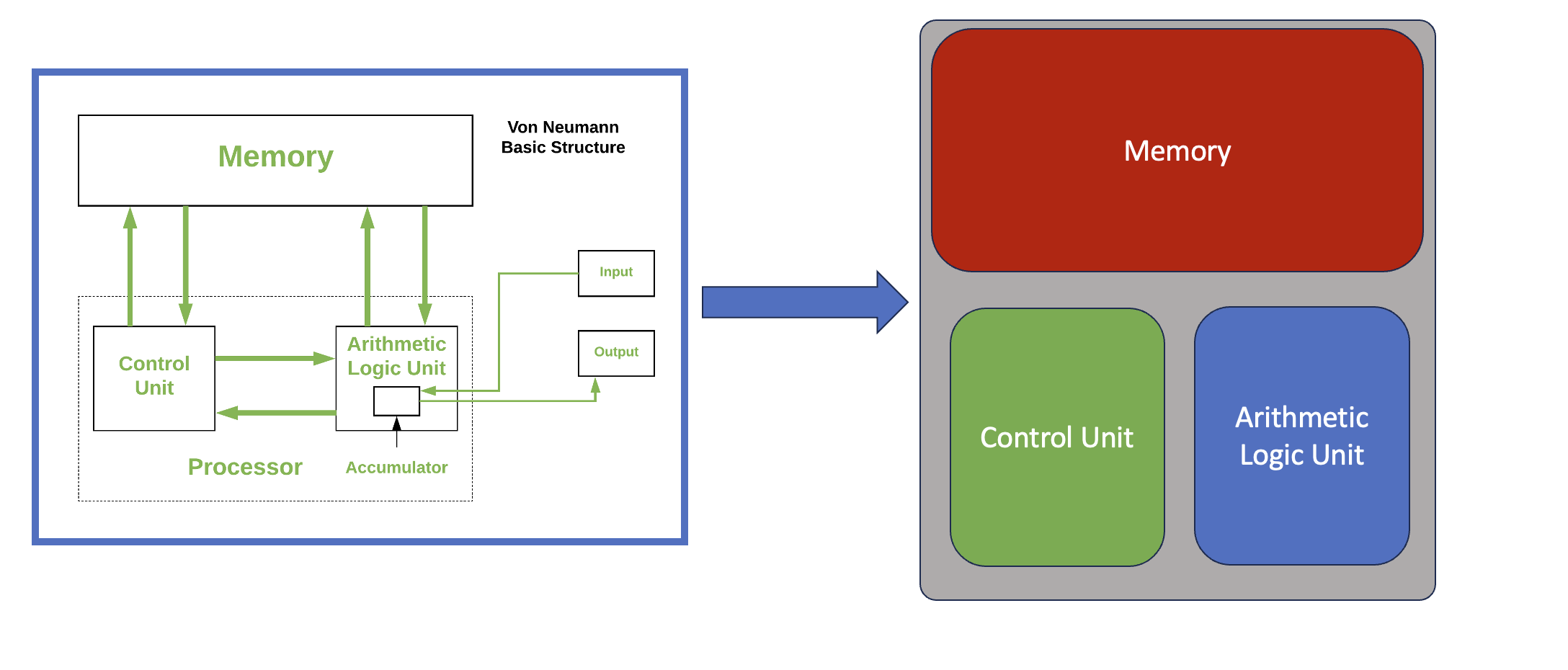

The von Neumann architecture

- A processing unit with both an arithmetic logic unit and processor registers

- A control unit that includes an instruction register and a program counter

- Memory that stores data and instructions

- External mass storage

- Input and output mechanisms

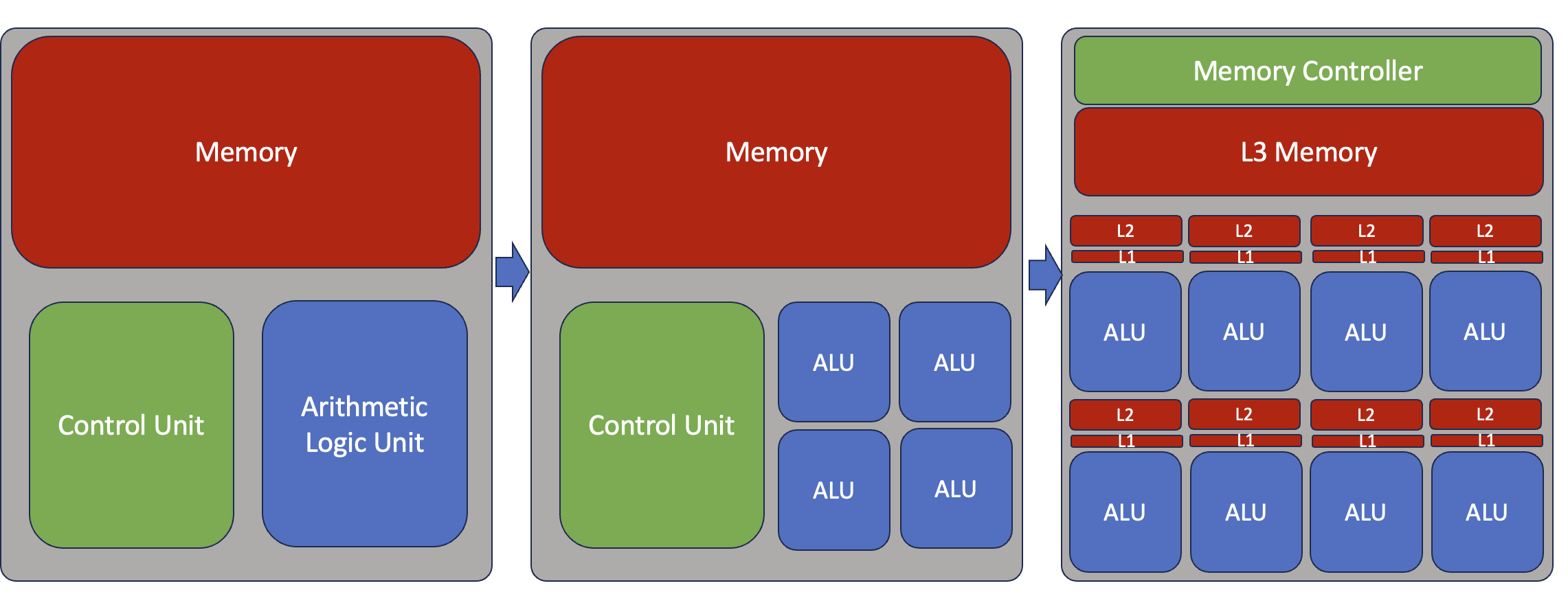

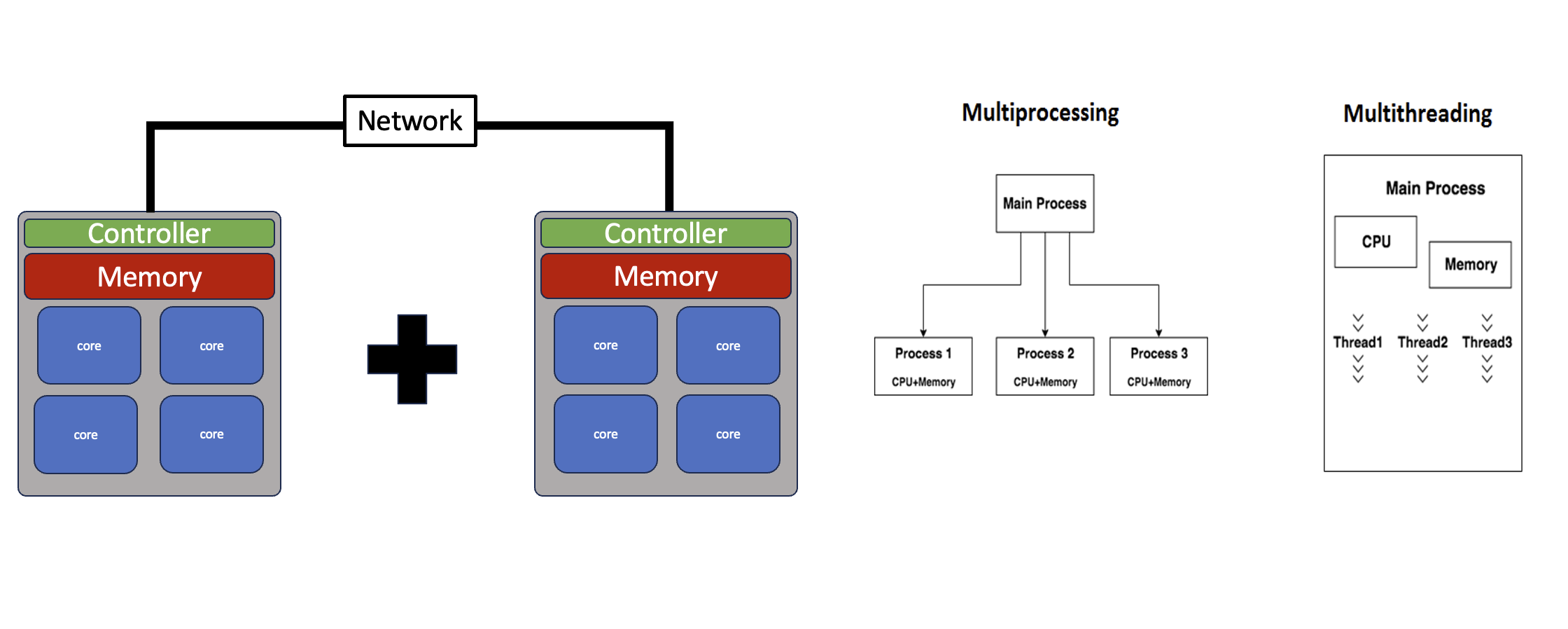

Simple multi-core cpu architecture

Challenge: How many logical cores (CPU cores) is located on the machine that you are running on?

Use the simple linux command lscpu to inspect the

specifications of the compute architecture that you are running on.

To make things a bit more complicated…. Because this class is taught

on shared resources, how many cores are actually allocated to this

specific notebook instance that you are running on? HINT: use the linux

tool numactl (specifically

numactl --show).

Solution

!lscpu!numactl --showThe Python Interpreter

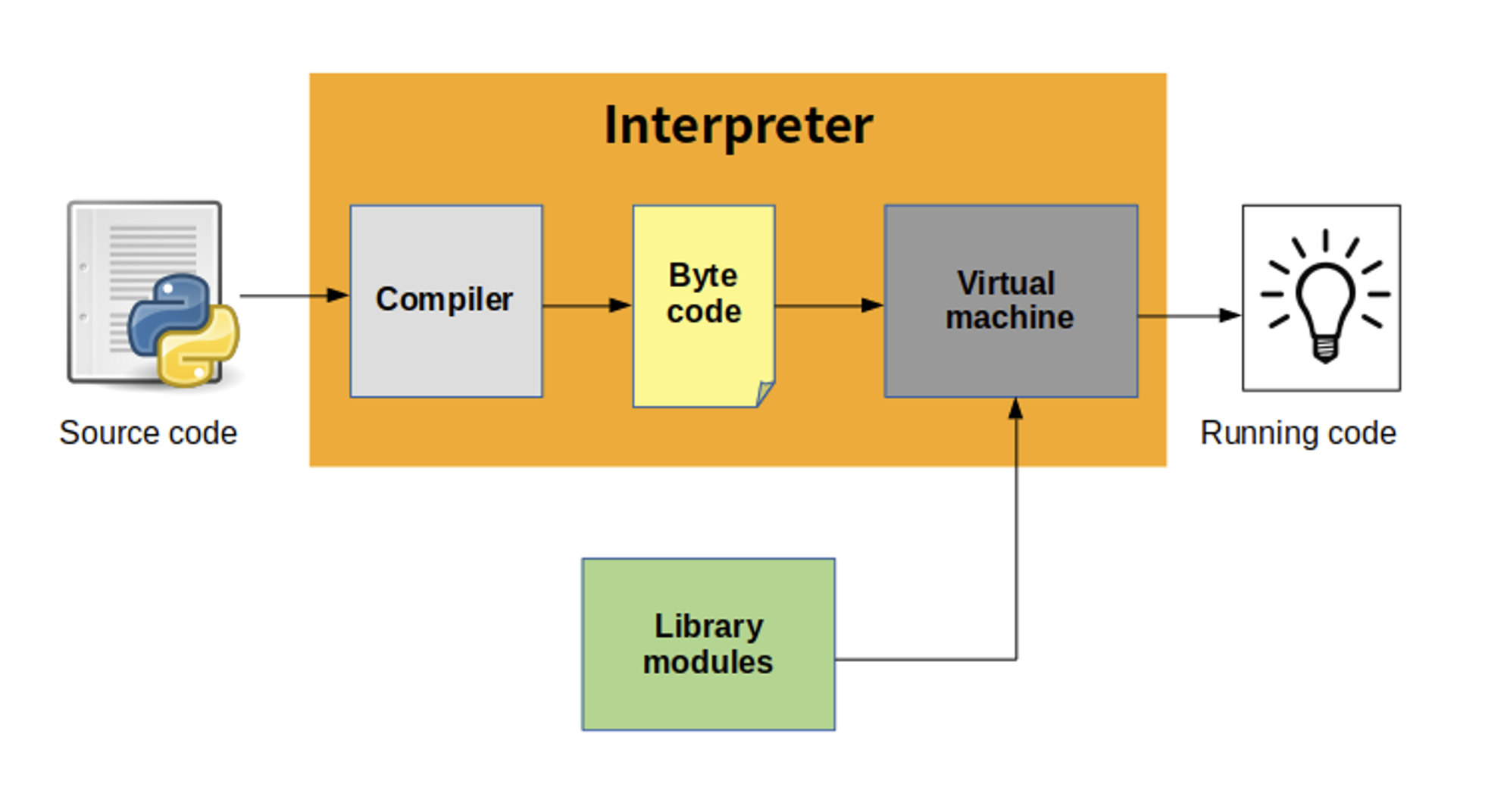

- Python source code is compiled into bytecode, the internal representation of a Python program in the interpreter.

- The bytecode is also cached in .pyc and .pyo files so that executing the same file is faster the second time (recompilation from source to bytecode can be avoided).

- This “intermediate language” is said to run on a virtual machine that executes the machine code corresponding to each bytecode.

The Global Interpreter Lock

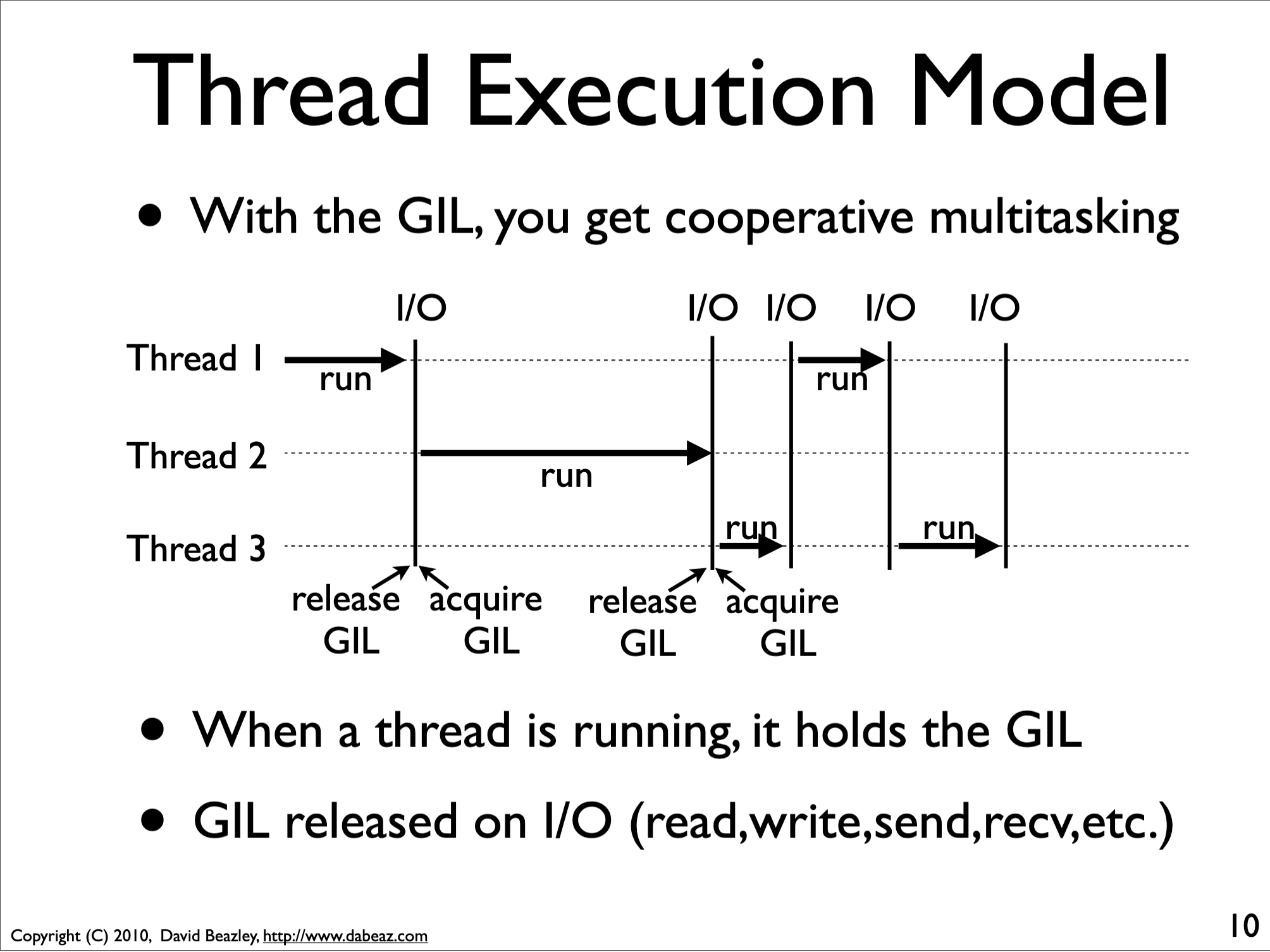

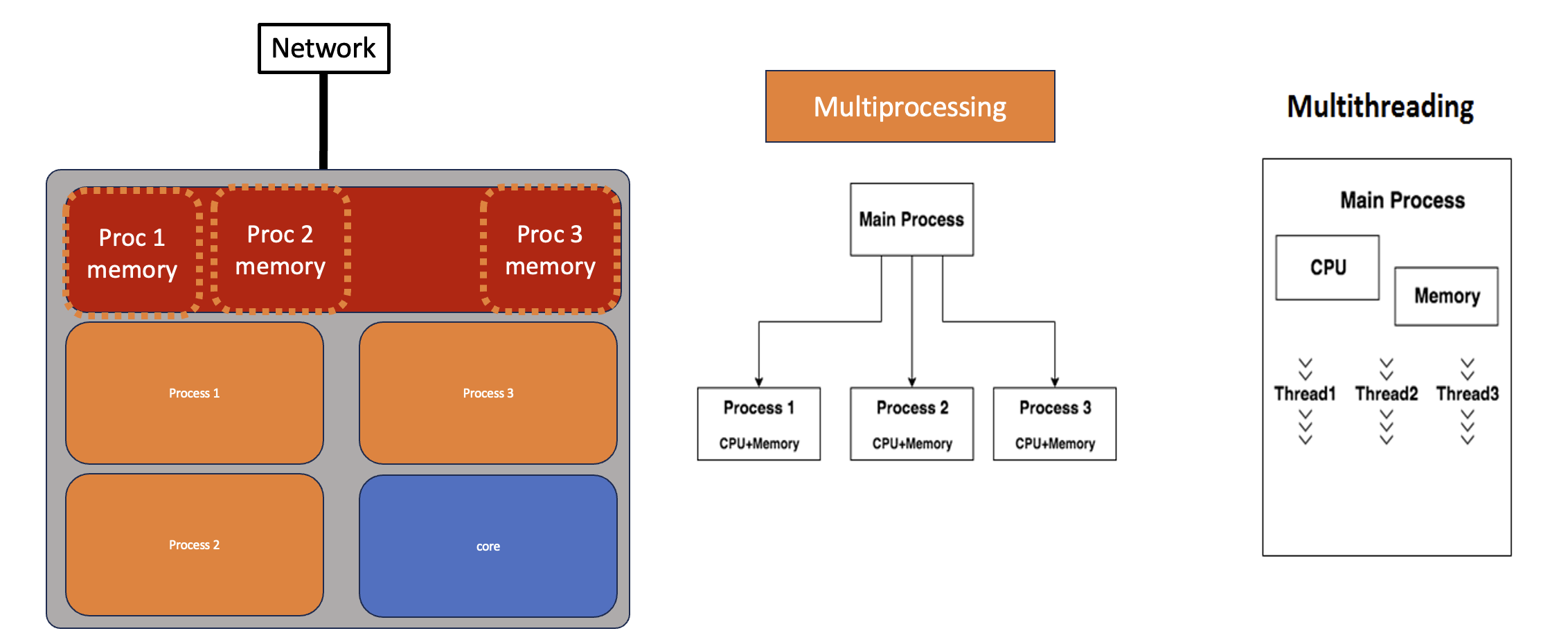

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) is an infamous feature of the Python interpreter. In CPython, theGIL, is a mutex that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple threads from executing Python bytecodes at once. The GIL prevents race conditions and ensures thread safety, making programming in Python safer, and prevents us from using multiple cores from a single Python instance.

When we want to perform parallel computations, this becomes an obvious problem. There are roughly two classes of solutions to circumvent/lift the GIL:

- Run multiple Python instances:

multiprocessing - Have important code outside Python: OS operations, C++ extensions, cython, numba

Threads, Processes and Python

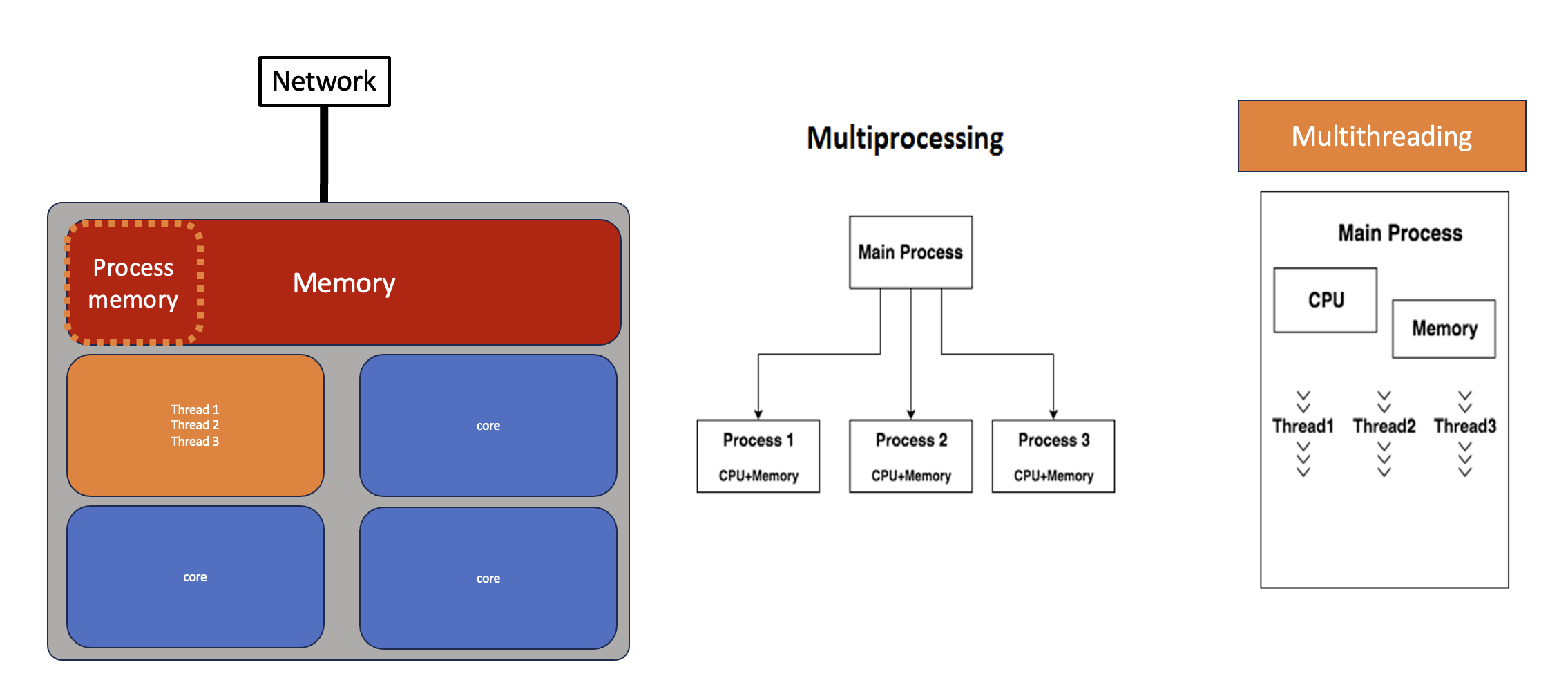

There are two basic implementations of parallelism in the Python Standard Library. Parallelism implemented namely via “threads” or “processes”

Thread example (via threading)

The threading module - includes a high-level, object oriented, API for working with concurrency from Python. Thread objects run concurrently within the same process and share memory with other thread objects. Using threads is an easy way to scale for tasks that are more I/O bound than CPU bound. The python threading module is used to manage the execution of threads within a process. It allows a program to run multiple operations concurrently in the same process space.

t1 = Thread(target=some_worker_func, args=(rnd1, ))Using threading to speed up your code:

import threading

import os

import time

def worker(worker_id):

"""thread worker function"""

time.sleep(worker_id)

print('Worker:',worker_id)t1 = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=[1])

t2 = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=[2])

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()- The

.start()method Starts the thread’s activity.- It must be called at most once per thread object. It arranges for the object’s run() method to be invoked in a separate thread of control.

- This method will raise a RuntimeError if called more than once on the same thread object.

- The

.join()method waits until the thread terminates.- This blocks the calling thread until the thread whose join() method is called terminates – either normally or through an unhandled exception – or until the optional timeout occurs.

Basic Exercises: Try to use the simple functionality of the threading module.

- Write a simple multi-threaded program that prints out the process

id, thread id, and thread names. Usefull methods to use

threading.current_thread().nameandthreading.current_thread().native_id. - Enumerating over all active threads. Usefull method

threading.enumerate(). Question, How many active threads are behind the Jupyter Notebook?

Solution

import threading

import os

import time

def worker(worker_id):

"""worker function"""

time.sleep(worker_id)

print("Thread name:",threading.current_thread().name)

print("Thread id:",threading.current_thread().native_id)

print('Worker:',worker_id)

print("PID:",os.getpid())

print("The number of active threads is:", len(threading.enumerate()))

print("And they are:",threading.enumerate())

print("\n")

print("\n")

t1 = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=[1])

t2 = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=[3])

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()Process example (via multiprocessing)

The multiprocessing - module mirrors threading, except that instead of a Thread class it provides a Process. Each Process is a true system process without shared memory, but multiprocessing provides features for sharing data and passing messages between them so that in many cases converting from threads to processes is as simple as changing a few import statements.

Multiprocessing is a package that supports spawning processes using an API similar to the threading module. The multiprocessing package offers both local and remote concurrency, effectively side-stepping the Global Interpreter Lock by using subprocesses instead of threads. Due to this, the multiprocessing module allows the programmer to fully leverage multiple processors on a given machine. It runs on both Unix and Windows.

The multiprocessing module also introduces APIs which do not have analogs in the threading module. A prime example of this is the Pool object which offers a convenient means of parallelizing the execution of a function across multiple input values, distributing the input data across processes (data parallelism). The following example demonstrates the common practice of defining such functions in a module so that child processes can successfully import that module.

p1 = Process(target=some_worker_func, args=(n,))Basic Exercises: Try to use the simple functionality of the multiprocessing module.

- Now re-write the code that prints out the process id, thread id, and

thread names but with

multiprocessing. What are the differences?

Solution

import threading

import multiprocessing

import os

import time

def worker(worker_id):

"""worker function"""

time.sleep(worker_id)

print("Thread name:",threading.current_thread().name)

print("Thread id:",threading.current_thread().native_id)

print('Worker:',worker_id)

print("PID:",os.getpid())

print("The number of active threads is:", len(threading.enumerate()))

print("And they are:",threading.enumerate())

p1 = multiprocessing.Process(target=worker, args=[1])

p2 = multiprocessing.Process(target=worker, args=[2])

p1.start()

p2.start()

p1.join()

p2.join()Concurrent Futures (easy solution for Threads/Processes)

Now that we have introduced the concepts of Threads and Processes in Python. Lets step back and use the concurrent.futures module. This module provides interfaces for running tasks using pools of thread or process workers. The APIs are the same, so applications can switch between threads and processes with minimal changes.

The module provides two types of classes for interacting with the pools.

- Executors are used for managing pools of workers.

- Futures are used for managing results computed by the workers.

To use a pool of workers, an application creates an instance of the appropriate executor class and then submits tasks for it to run. When each task is started, a Future instance is returned.

ThreadPoolExecutor, ProcessPoolExecutor

ThreadPoolExecutor is an Executor subclass that uses a pool of threads to execute calls asynchronously. ThreadPoolExecutor manages a set of worker threads, passing tasks to them as they become available for more work.

This example uses map() to concurrently produce a set of results from an input iterable. The task uses time.sleep() to pause a different amount of time to demonstrate that, regardless of the order of execution of concurrent tasks, map() always returns the values in order based on the inputs.

tasks = range(1,5)

ex = futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=len(tasks))

results = ex.map(some_worker_func, tasks)Exercise: adapt the original exercise to submit tasks to a pool

- Try launching a pool of threads vs processes

Solution

import threading

from concurrent import futures

import os

import time

def worker(worker_id):

"""worker function"""

time.sleep(worker_id)

print("Worker:", worker_id)

print("PID:",os.getpid())

print("Thread name:",threading.current_thread().name)

print("Thread id:",threading.current_thread().native_id)

print("The number of active threads is:", len(threading.enumerate()))

print("And they are:",threading.enumerate())

tasks = range(1,5)

ex = futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=len(tasks))

results = ex.map(worker, tasks)Protect process creation with an if-block

A module should be safely importable. Any code that creates processes, pools, or managers should be protected with:

if __name__ == "__main__":

...Exercise: Write calc_pi to be caculated using the .map() method.

- Try launching a pool of threads vs processes.

- Whats the speed up? Are there benefits with Threads v Processes?

Solution

import time

import random

import numpy as np

from concurrent import futures

def calc_pi_map(N):

M = 0

for i in range(N):

# Simulate impact coordinates

x = random.uniform(-1, 1)

y = random.uniform(-1, 1)

# True if impact happens inside the circle

if x**2 + y**2 < 1.0:

M += 1

return 4 * M

resolution = 10**6

num_workers = 2

p_start = time.time()

ex = futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=num_workers)

# or

# ex = futures.ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=num_workers)

results = ex.map(calc_pi_map, [resolution for x in range(num_workers)])

final_results = list(results)

p_end = time.time()

print("Resultion:", np.mean(final_results)/resolution - np.pi)

print("Execution:", p_end - p_start)Discussion: where’s the speed-up threads vs processes?

While mileage may vary, parallelizing calc_pi,

calc_pi_numpy and calc_pi_numba this way will

not give the expected speed-up. calc_pi_numba should give

some speed-up, but nowhere near the ideal scaling over the

number of cores. This is because Python only allows one thread to access

the interperter at any given time, a feature also known as the Global

Interpreter Lock.

The GIL in action

The downside of running multiple Python instances is that we need to

share program state between different processes. To this end, you need

to serialize objects. Serialization entails converting a Python object

into a stream of bytes, that can then be sent to the other process, or

e.g. stored to disk. This is typically done using pickle,

json, or similar, and creates a large overhead. The

alternative is to bring parts of our code outside Python. Numpy has many

routines that are largely situated outside of the GIL. The only way to

know for sure is trying out and profiling your application.

To write your own routines that do not live under the GIL there are

several options: fortunately numba makes this very

easy.

- If we want the most efficient parallelism on a single machine, we need to circumvent the GIL.

- If your code releases the GIL, threading will be more efficient than multiprocessing.

- If your code does not release the GIL, some of your code is still in Python, and you’re wasting precious compute time!